They are Us: Mark Aitken’s Dead When I Got Here

“He’s a poet,” said Aitken about Josué, “nothing less than a poet. None of [the film] was scripted, he just came out with those lines. I’ve recorded hours with him and there’s a lot more besides.”

Josué has a very dark past, and spent decades in prison for his involvement with drugs. He has now found solace in his work at the asylum and, through the documentary, has been reunited with his daughter.

This film is not, however, about redemption. “I don’t believe in redemption,” said Aitken, who told the Frontline Club audience that he was keen to avoid a clichéd Hollywood narrative. “If this was a Hollywood version you’d have Josué playing with his grandchildren and running [a franchise of asylums]. But it’s not,” he said.

One of the motivations behind the film was to show the connection between us in the West and those who we perceive as being ‘others’.

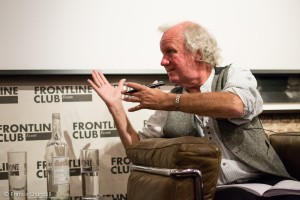

Mark Aitken

Vulliamy was keen to stress the economic connection that globalised capitalism creates between the developed world and places like Juárez.

“Juárez is… the carberetor under your car, it is the electronics in your mobile phone. It’s all made, if not there then in places like that,” said Vulliamy. “We’re not watching another world, are we Mark? We’re watching very much a part of our lives.”

There is an exploitative relationship, Vulliamy argued, which is shown in films like this one. “They make us,” said Vulliamy, referring to the town’s manufacturing past, “and we use them.”

Aitken told the club that initially he was somewhat scared of the patients at the asylum, but he gradually grew to respect them. “These are survivors,” he said, “they could teach us a few things.”

“You know we’re just more fortunate, that’s the only difference. So this ‘us and them’ dichotomy of us somehow being superior because we’re comfortable is all back to front. It’s the wrong way round,” said Aitken.

Making the film was very challenging for Aitken. The act of filming itself was easy, even ideal, a she only ever had one complaint from the patients. “Most people tended to repeat their actions…”

Ed Vulliamy

Daily life at the asylum was likewise very repetitive, giving Aitken the opportunity to get the shots he needed. “Every day they do these routines, so every day I filmed the same thing, the same people, and I could film it in different ways. And once I’d exhausted it I would move on.”

The difficulty came in the responsibility that he had as a filmmaker to ethically tell the patients’ stories. The people that he was filming were very uninhibited. “They haven’t really got the capacity to say ‘no, fuck off, don’t film me,’” said Aitken, “… I don’t want to just be a voyeur here, I have to do something with this and show them in a particular way.”

What Aitken wanted to show is that we are the same as the people in the asylum, and that we are also all connected.

“If we’re constantly told that we’re different, and the trouble is over there and not here, then it make us feel better,” said Aitken. “Maintaining that fear is very much to do with, ‘well, look at them over there, they’re falling off boats trying to get to Italy from Africa… lucky it’s not you’.”

There is reluctance, both Vulliamy and Aitken agreed, to accept that poverty and drug money are directly connected.

“I mean this seems to be the huge… why it’s not ‘them and us’, why we are them. The money out of that misery [in Juárez and similar environments] is being spent on the golf courses of Connecticut and in the wine bars of Holland Park and Canary Wharf,” said Vulliamy.

“There is this kind of abyss that you [Aitken] and I spend our lives trying to cross, trying to tell people, ‘this is you and you are it’,” he said.

Mark Aitken (left) and Ed Vulliamy