An Evening with Molly Crabapple: Drawing Blood

The craft of drawing has an important role to play in shining a spotlight on the people and places left unseen.

Artist and journalist Molly Crabapple joined an audience at the Frontline Club on Wednesday 6 April to discuss the unique purpose of her art in uncovering injustice and activism around the world. She also held a book signing session for her recently released memoir Drawing Blood, a colourful mix of autobiographical writing and illustrations.

How to draw censorship, how to draw the unseen? Great talk by @mollycrabapple at @FrontlineClub

— Veronique Mistiaen (@VeroMistiaen) April 6, 2016

Starting out as a model and artist in the sex industry, Crabapple has gone on to draw and report from Guantanamo Bay, Syria, the West Bank, Iraqi Kurdistan, and became a crucial voice during New York’s Occupy Movement in 2011. Long-time friend and journalist Natasha Lennard joined Crabapple to chair the discussion, describing her as “a crucial voice of our time, in a moment when journalism is in flux and open for necessary experimentation.” Lennard began by asking her motivations for using art for journalistic purposes.

“Photojournalists, they went into the world and captured everything, captured a story, they captured all these people and all these places,” Crabapple replied. “And I thought, my god, we artists used to do that before the camera came. The camera stole the image-making power from us. And I wanted to do that too.”

Her first assignment as a journalist was in 2013, when she visited Guantanamo Bay to document the detention centre and its inmates. Later that year, she was shortlisted for a Frontline Award for her stark portrayal of the prison, and the anonymous figures locked within its walls.

By Molly Crabapple

“Guantanamo is the most visually censored place on earth,” she explained. “Guantanamo is a place that if you were a photographer, your camera would be rifled through by a soldier at the end of every single session. But… I was able to draw Guantanamo Bay in a way that a photographer cannot photograph it. Not only that, but to draw the censorship itself. To make it explicit.”

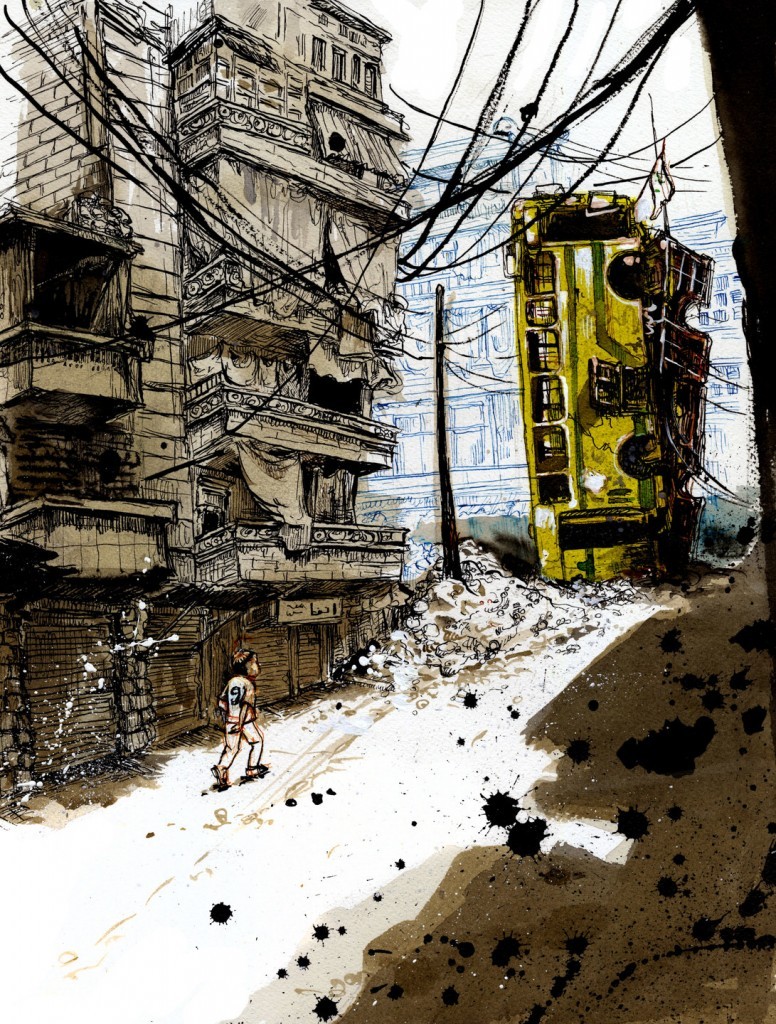

Continuing on the theme of censorship, the duo turned to Crabapple‘s work with a Syrian journalist in Raqqa in 2015. She created a series of illustrations from photographs sent from Syria for Vanity Fair showing daily life under ISIS rule, areas too dangerous for most photojournalists to access.

“One of the projects that I’m proudest of was this project I did with a young Syrian writer named Marwan Hisham,” Crabapple elaborated. “I wanted to take images of daily life from ISIS-held territory and not the usual gory images of severed heads that we see on the news. Images of children going through the trash trying to find something to sell, or images of families on breadlines. Images of just daily prosaic life there. I wanted to, with my own skills as an artist, imbue them with craft and all the attention and time that a photojournalist would normally view something with.”

By Molly Crabapple

One audience member asked, given the traumatic and sometimes horrifying nature of the material she was dealing with, how drawing Syria had affected her.

Crabapple replied: “I am completely in awe of courage, of Syrian journalists working in the field, and the intense risks that they take… No one even cares if they die. It’s staggering and I feel a sense of shame. That’s how it transforms me, it gives me a sense of shame because in many ways my collaborators are better than me.”

Throughout the evening, many people in the audience expressed gratitude to Crabapple for her work, adding that it encouraged them to explore politics, human vulnerability and activism through art. After thanking her, one audience member asked Crabapple how she would imagine an ideal world.

“I think we are facing a fundamental challenge to the idea of borders,” Crabapple responded. “I think with the internet and the way people interact globally, that the way people are chained if they have ‘poor-world passports’, despite these global interactions that they have… I think that cannot stand. The ‘First World’ is going to have a choice– to either be part of the rest of the world, which they’ve often been exploiting… or they can engage in massive violence to keep the rest of the world out. I fear very desperately that they’re going to choose the second. But a small step toward making the world better might be them choosing the first.”